The changing rate of rate change

Finance professionals have a horrible tendency to speak in financial code. Their technical-speak is sprinkled with jargon and acronyms, in an attempt to convince clients of their unmatched sophistication and experience.

Apologies to my fixed income peers, but one area particularly prone to the overuse of jargon is bonds. So much so that even seasoned investors lose the plot after a few minutes listening to a spirited bond investor.

I’m not saying the sophistication isn’t rewarded in fixed income: at Human Financial we’re firmly of the view that bond markets are inefficient, and thus an active approach is rewarded. What I am saying, though, is that we need to be better at explaining what really matters for investors and the economy.

So here goes…. Eleven times a year in Australia, and eight times a year in the US, the board of the central bank meets to set interest rates. The rate they set is what is commonly referred to as the “overnight rate” which equates to the interest rate they receive on the cash in their bank accounts. From there, lenders (banks) incorporate a number of variables into their setting of mortgage rates, including: policy, growth rates, inflation and the overall outlook of the housing market.

And of course, what matters to most people is the mortgage rate they have to pay to own their dream house. More broadly, what matters are the interest rates charged on all loans, from personal through to business loans. These loans drive the economy, through the continuous growth cycle of borrowing, consumption and repayment.

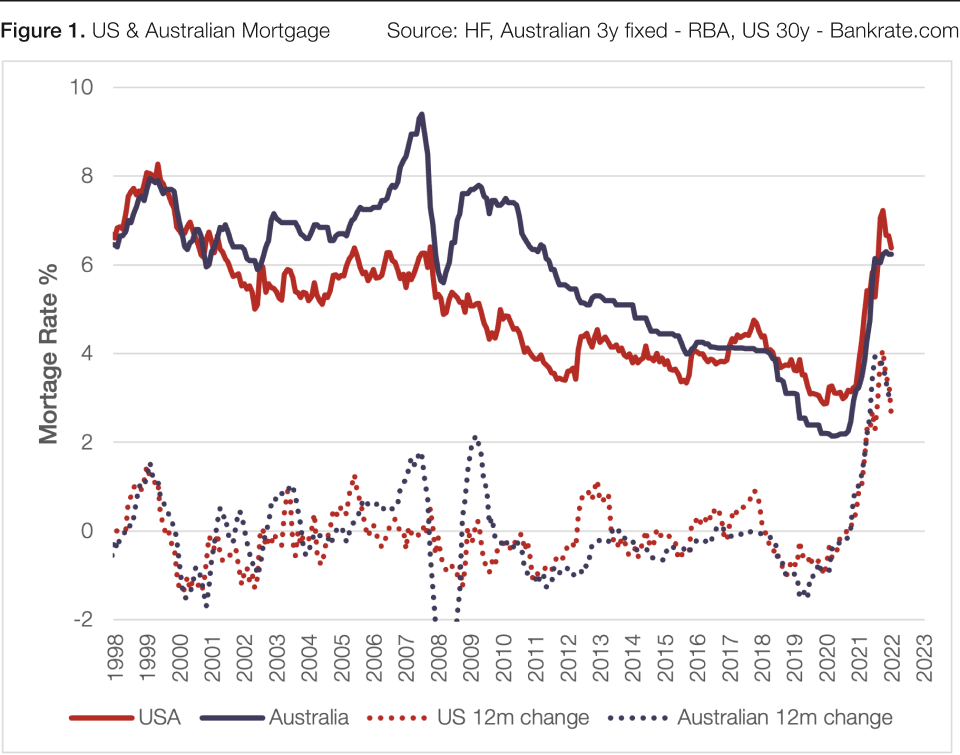

Figure 1 shows US and Australian mortgages over the past quarter-century and how they tend to move in the same direction. Two elements of loans matter: the actual level as well as the rates of change. The higher the level or the more frequent or larger the changes, the more uncertainty that a borrower and lender must incorporate into their decisions.

Mortgage rates both here and abroad are now back at levels last seen during the 2000s: in isolation this is manageable. But the potentially more destabilising and uncertain aspect of current mortgage rates is the change we’ve experienced to get here. The 12-month change is more than double anything else witnessed within a generation and it’s not certain that central banks are finished yet.

This uncertainty adds risk to any long-term financial decision – like buying a house – and will therefore most likely shift the housing sector from economic tailwind to headwind in quarters to come. And it is likely to stay that way until borrowers have a greater level of comfort about the course of action central bankers are likely to take.