On patience and persistence

As much as anything, investing is a game of patience. And patience can be tested when you’re swimming against the tide of market consensus.

We’ve long been of the view that big, negative, slower-moving economic currents have yet to be appreciated by the markets – a view reflected in our tactical wealth preservation approach. This approach continues to be rewarded, with our downside protection outperforming our peer group in October.

In equities, all major markets were down over the month. Europe was the worst performer, with Switzerland -5.2%, Germany -3.7% and France -3.8%. Somewhat surprisingly, the technology-heavy US markets of the S&P 500 and Nasdaq sold off less heavily, with returns of -2.7% and -2.0% respectively. Within the US, all sectors were lower over the month, with the energy sector the biggest laggard at -6.1%. The traditionally defensive utilities sector was the outlier, up +1.2% over the month. Meanwhile in Australia the ASX200 was a poor performer, down -3.8% with large dips in healthcare -7.1% and industrials -6.2%.

Bond yields resumed their climb in October as the combination of budget deficits and renewed inflationary concerns reinforced investors’ continued dislike for government bonds. Australian bonds were the worst performers: 10-year yields rose 0.44% to reach 4.99% as stronger economic data suggested the RBA may need to increase interest rates further to suppress elevated inflation levels.

One factor that could be contributing to the current selloff is the increased selling of bonds by central banks around the world, as they continue to shrink their balance sheets. Following the GFC central banks bought predominantly domestic government bonds in various programmes in what is collectively termed “quantitative easing” (QE). QE programmes had two major benefits:

Increased confidence: Central banks stepped in as ‘buyers of last resort’ providing cheap and effectively unlimited financing to commercial banks with flow-through effects to corporates and consumers;

Increased liquidity: This then released private funds usually required to fund government borrowing (by buying bonds) for reinvestment elsewhere in the economy.

Today, most major central banks (apart from China’s PBOC and Japan’s BoJ) are in the process of reversing that policy and are shrinking their balance sheets.

This in turn reduces the liquidity in the market as other (private) investors are required to step in and purchase the government bonds that previously were held by the central banks. This creates a ‘crowding-out’ effect as investible funds are channelled towards government borrowing rather than towards investments in companies and future economically-productive investments. Effectively there is less money to go around and the government always funds itself first.

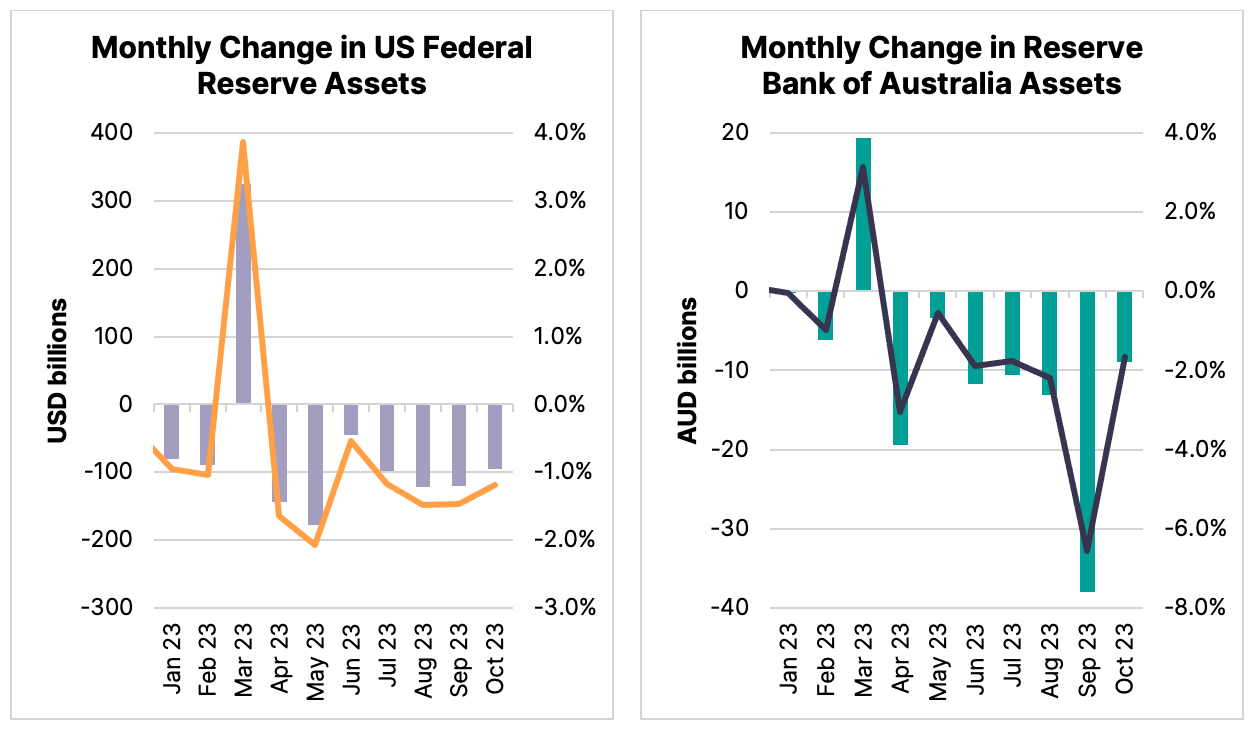

The chart below shows the monthly change in major central bank balance sheets. In general, they have been contracting by 1-2% each month through the bond interest payments which they do not reinvest. There was a spike in March 2023 when the US Federal Reserve pumped liquidity into the banking system to avoid contagion from the Silicon Valley Bank collapse. More recently the RBA has been reducing its balance sheet by c.2% each month; however, this increased dramatically in September with the maturity of the first tranche of the Term Funding Facility (TFF). The TFF was a Covid-era policy tool to ensure Australian banks had sufficient access to capital: this is now being wound up in tranches until June 2024.

Historically, liquidity withdrawals tend to be slow then fast, in that the cumulative effect is always increasing while the number of larger bond or programme maturities also increases. Potentially compounding the issue is the combined effect of most central banks having similar policies in place (buying fewer bonds) while most governments are increasing their bond issuance (borrowings) to pay for higher interest costs and the continued impact of budget deficits (selling more bonds).